By KATIE SKELLY

The 1973 adult animation feature film Belladonna of Sadness (Kanashimi no Beradonna) was birthed into the world by Mushi Productions, the animation production studio founded and eventually abandoned by Osamu Tezuka after the commercial failure of his own adult animation feature, Cleopatra (1970). In the 90-minute film, directed and co-written by Eiichi Yamamoto, the virginal protagonist Jeanne lives a peaceful, humble life in her feudal village until a sadistic baron violates her by rule of droit du seigneur on the eve of her wedding. The destitute Jeanne begins to experience visions of a phallic demon, who strikes a deal with her and brings her closer to power through manipulation of nature and magic.

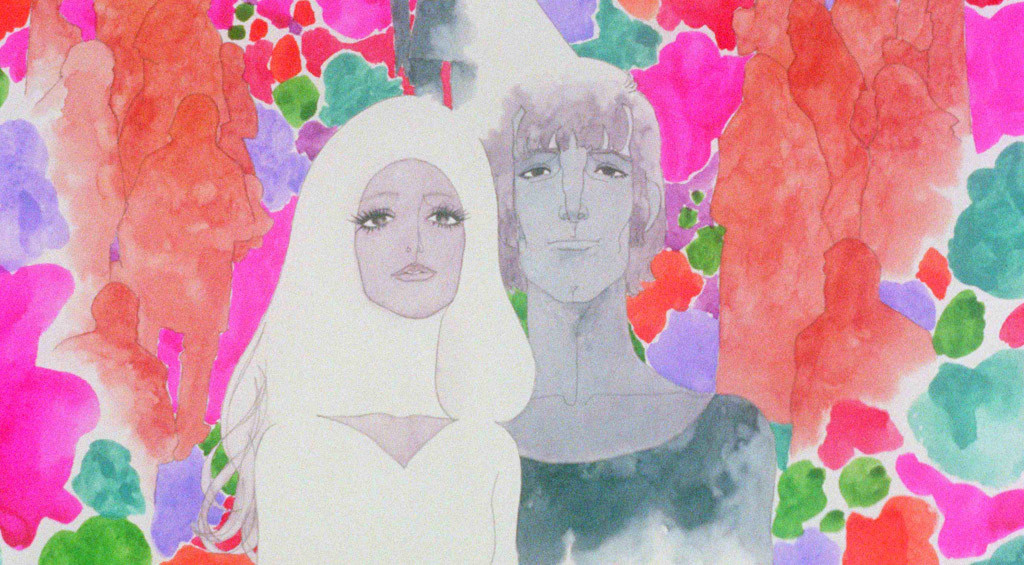

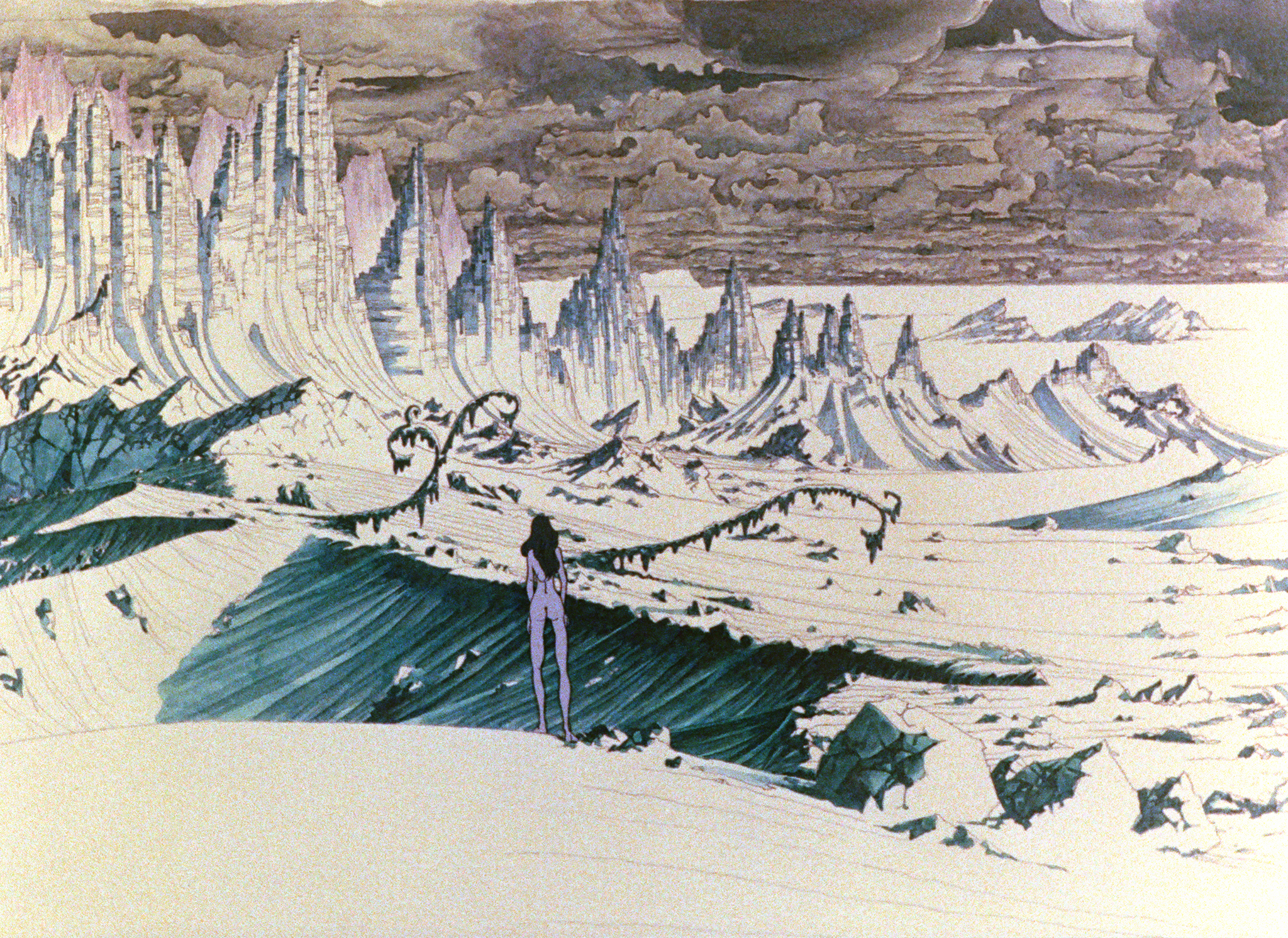

Belladonna, like Tezuka’s Cleopatra, was a commercial failure and remained unseen by wider audiences for years after its initial release. However, its lurid themes of eroticism, explicit sexuality, and witchcraft—the film takes cues from Jules Michelet’s 1862 treatise Satanism and Witchcraft—combined with its eye-watering psychedelic stills garnered steady interest in the age of the internet. After over 40 years of obscurity (and endless low-quality versions surfacing online), Belladonna of Sadness recently received a 4K restoration by Los Angeles-based post-production company Cinelicious. Having recently seen the restoration myself after years of anticipation, I was thrilled by its slow and steady animation style, reminiscent of the language of comics, its thumping soundtrack and painterly style, which I had never seen in animation prior.

I spoke to members of the Cinelicious team (Craig Rogers, lead restoration artist; Caitlin Diaz, remastering colorist, and Dennis Bartok, executive vice president of acquisitions and distributions) about the genesis of the restoration, the challenges of the project, and their thoughts on the future life of Belladonna.

Katie Skelly: How did you and Cinelicious come to work on the restoration of Belladonna of Sadness?

Dennis Bartok: The restoration and re-release of Belladonna of Sadness actually came out of an informal lunch in Spring of 2014 here at the Cinelicious offices with Hadrian Belove, founder and head of The Cinefamily non-profit film organization in Los Angeles. I asked Hadrian, “If you could restore any rare or unknown films which would you pick?” — and the first one he mentioned was Belladonna of Sadness. (I should add that The Cinefamily is co-presenting the re-release of the film with Cinelicious Pics here in the U.S. along with Spectrevision.) Although I’m a huge fan of Japanese cinema including anime, and had shown literally hundreds of rare and classic films while I was head of programming at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre, I’d never seen or even heard of Belladonna — which is some indication of just how far off the radar it is! I watched a pretty fuzzy, dupey version illegally posted on YouTube and was immediately blown away by the mixture of eroticism, psychedelia, and the occult, along with the phenomenal fuzz-stoked soundtrack by Masahiko Satoh. Since the film had never been released on the U.S., I started a detective search to track down the rights holder in Japan: through a colleague in Germany, Andreas Rothbauer, I was put in touch with Stephan Holl at Rapid Eyes Movies there who’d released Belladonna on DVD in Germany and France — Stephan kindly gave me contact info for Kiyo Joo at Gold View Company in Japan, who represents Mushi Productions, the original production company for the film.

Craig Rogers: For Belladonna of Sadness I was the guiding hand moving the project along and did a great deal of hands on work digitally cleaning up our 4K scans (along with Michael Coronado, another restoration artist at Cinelicious). While we were lucky to be able to scan the original negative – and for the most part the negative was in very good shape – there was still a tremendous amount of work involved in getting the images looking as clean as possible. Fixing scratches, removing dirt, reducing and/or eliminating flicker and stabilizing the images – we went over each and every frame and manually cleaned up all of these issues. One thing we did not do was overly degrain or sharpen the images. Scanning at 4K from the original negative is already going to give us beautiful sharp images, there’s no good reason to sharpen them further – and film has grain. Period. A forty-plus-year-old animated film shouldn’t look like it was created digitally in 2015.

Caitlin Díaz: Knowing my love for the ultra-weird and experimental side of cinema, Dennis Bartok recommended I watch the Belladonna of Sadness screener we had in the office. After watching the film a few times, I knew it would be a fun and challenging project to take on. When news broke that we had secured the rights for a 4K restoration and a U.S. redistribution of the film, I told Paul Korver I was interested in doing the color remastering for the film. When the film elements arrived at our office, we all wanted to know what condition they were in. While prepping the film with film leader and labeling the reels, I noticed the film was in pretty good condition. However, I did see that there were some splices made throughout–little did we know we didn’t have the entire version of the film. After the film had been cleaned using our Ultra Sonic Film Cleaner, I began to scan the reels. We wanted to scan at 4K to take advantage of the high dynamic range and resolution that a 35mm camera negative offers. As I watched the film play out on the monitor, I gathered a sense of the color and textures in each scene–I couldn’t wait to start grading!

What were the unique challenges to restoring Belladonna?

Dennis Bartok: The biggest initial challenge was simply convincing Gold View Co. and Mushi Productions to send the original camera negative and sound elements to us in Los Angeles. The original negative had never traveled outside of Japan to my knowledge, and they were understandably very concerned about sending it to us. At one point they offered to make a new print off the negative and ship that to us, but we were really insistent on getting access to the 35mm negative if we were going to commit all the time, manpower and money to restore the film in 4k. It took months of alternately pleading, waiting, pleading some more until we finally convinced Gold View and Mushi to trust us with the negative and sound elements. They literally emptied their Belladonna vault out, and sent everything they had to us. We were all pretty ecstatic when we finally received the negative after so many months of back and forth. As Craig Rogers mentions, the negative itself was in fairly good condition, which was a great relief — but we were a little shocked to discover it had been cut down by approximately 8 minutes and those sections lost or destroyed. Each reel of negative was literally peppered with white tape splices indicating footage that was missing. We’re still trying to 100% confirm why the negative was cut this way, but in an interview with director Eiichi Yamamoto recently, he recalled that that the film was cut down sometime after its initial, unsuccessful release, apparently in an attempt to produce a version with less graphic eroticism that would appeal to younger female audiences. From what we can tell this censored version was never released, since the filmmaker and producers realized after watching the edited version that the real spine and biting edge of the film had been cut out as well.

Craig Rogers: Just getting our hands on the original negative was a challenge! Another challenge became evident when we were prepping that negative for scanning. Caitlin discovered that about 8 minutes of the film had been edited out of the original negative. We had a very poor quality digibeta tape we were using as reference for conforming the project and needed to use that to figure out what exactly was missing. Sometimes it was just a few frames from a shot, but in other cases it was long sequences that had been removed.

Dennis, with the help of acquisitions director David Marriott, were able to track down what we believe is the only remaining 35mm print of the original uncut film at the Cinematek in Belgium. The folks at Cinematek were very helpful in providing us with scans of the missing sections from their print. That required a lot of effort to get the two elements to work seamlessly in the film. French subtitles needed to be removed and we wanted to be sure there would not be an obvious jump in the picture (both physically and in quality) where we cut in the Belgium print footage. I’m very proud of our team’s work in accomplishing this. I believe a great many of these cuts will go completely unnoticed by the viewer!

Grading the film with little more than a few reference stills from the production was also a challenge, which I worked closely with Caitlin Diaz trying to get it just right. Caitlin did a stellar job. We’d love to have been able to have director Eiichi Yamamoto here with us when we did the grade, but he could unfortunately not make the trip from Japan. We’ve sent him samples of our final restoration and he’s delighted with how gorgeous his film looks.

Caitlin Díaz: You’d think that the color grading process would be pretty straight-forward since Belladonna is an animated film–this wasn’t the case at all. Our only reference for this film was a DigiBeta master which was extremely faded and had an overall blue/purple tint. Once I started working with the scans from the original camera negative, it became clear that the colors were drastically different from the reference. Luckily, Mushi Productions provided a few images of the artwork, which proved very helpful in figuring out what the colors were supposed to look like.

The film is full of different styles of animation all using different mediums and the grade needed to remain true to each. The watercolors needed to be vibrant, but not extremely contrasted. The oil paint needed to have the depth and texture of each brushstroke. One of the most challenging aspects of the grade would have to be matching our camera negative to the 35mm print inserts we received from the Belgium Cinematek. The print is a few generations from the original negative, which causes sharpness and color information loss. Before, when we cut from the camera negative to the print in the same shot, you’d notice a stark difference. I tried out a few different approaches when it came to these back-to-back cuts and I was able to arrive at a place where the color shift was subtle. With these color adjustments combined with Zach Roger’s amazing repositioning and conform skills, we were able to remove the distraction caused by the difference in elements and allow the viewer to remain in the realm of the film. We spent three days locked up in our DI theater finessing each scene and frame, making the cuts between each shot play together seamlessly. It was important to have extra sets of eyes during these last few sessions, especially since we couldn’t get Eiichi Yamamoto to join us. I was able to dial-in the final looks, a process with which Craig Rogers was extremely helpful. His attention to detail in his restoration work definitely carries over to the color world! I’m very pleased with how the film looks now that the all the work is complete–we pooled our various talents and resources to bring Belladonna back into the fold at a level of beauty and detail it very much deserves.

The commercial failure of Belladonna of Sadness contributed to the bankruptcy of its animation studio, Mushi Productions, in 1973. Do you think audiences are better equipped to appreciate this film today, and if so, why?

Craig Rogers: Dennis can likely speak more in depth, but it’s been my understanding that Mushi’s fate was already sealed by the time Belladonna of Sadness was in production and in fact may be why Belladonna of Sadness was able to push the boundaries of anime as far as it did. Similar to Stan Lee’s telling of how Spider-Man came about in Amazing Fantasy #15. If the ship is going down, you might as well use it as an opportunity to try something new!

A lot has changed since 1973. That said, Belladonna of Sadness still pushes things pretty far. Particularly for American audiences, some of the sexual imagery will still shock people. I think a great deal of that explicit imagery was used purely for fun and to titillate, but the tougher scenes to watch are intentionally tough. What this woman endured is a large part of the story. I know this film is often described as an “art film”, which in my experience has usually meant “weird and boring.” I was really worried that this would be the case here, but after seeing it I was blown away. It is an “art film”, but it also has a coherent and important story to tell. Along with the astounding artwork, there’s a tremendous amount going on thematically. Questions of “what is evil?,” the corrupting influence of power, and feminism.

Dennis Bartok: Belladonna of Sadness was the third and final film in the adult-oriented “Animerama Trilogy” produced by Mushi Productions from 1969 to 1973. All three films are very different stylistically although they were all directed by Eiichi Yamamoto (Osamu Tezuka co-directed the second, and least interesting one, Cleopatra.) In an interview we conducted recently with Yamamoto for the Blu-ray release of Belladonna and a companion book we’re doing, he mentioned George Dunning’s Yellow Submarine as an inspiration for the creative team on Belladonna, and you can definitely see the influence especially in the surreal and outrageously erotic “dream sequences” towards the end of the film with humans and animals morphing into grotesque phallic forms. Ironically, the first two films in the “Animerama” series, One Thousand & One Nights and Cleopatra, did get released in the U.S. aimed at a grind house audience — but I think Belladonna of Sadness, by far the most visually spectacular and groundbreaking of the three films, was simply too far out there for distributors in America in the early 1970s. It’s a shame because if it had come out then aimed at an art-house and underground cinema crowd, I think it could have found a cult audience similar to Rene Laloux’s Fantastic Planet or Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards. It’s funny that we’re doing the first “official” U.S. release of the film over 40 years after it was made, so in some ways it’s a new film for American audiences. I think the pure visual splendor and overwhelming beauty of the artwork done by Kuni Fukai has remained incredibly fresh, along with the avant garde psychedelic score by Masahiko Satoh. For me, the most interesting thing about seeing audience reactions to the restored film so far is that it’s still dangerous and disturbing especially the imagery of sexual violence depicted in the movie. The source novel the film was based on was a parable about the vulnerability and powerlessness of peasants, especially women, in the Middle Ages — and director Yamamoto and artist Fukai were definitely aware of that underlying theme. Not to give anything away, but the end of the film certainly underscores that Belladonna of Sadness is a story about the abuse of women and their ultimate empowerment and rising up to overthrow the status quo.

Caitlin Díaz: While Belladonna may have gotten lost in the mix of psychedelic cinema of the ’70s, I feel that its rerelease will not only capture the interest of animation aficionados, but also find a new audience in those who seek films that go beyond the norm of our era. Our restoration really breathes new life into this lost film. By celebrating Kuni Fukai’s intricately hand-drawn artwork and Masahiko Satoh’s brilliant original score, we are sharing a film that is not only aesthetically pleasing, but also layered with themes of power, gender politics, and history. I’m very much looking forward to hearing what people think ofBelladonna forty-plus years after its original release!

Screenings begin this week.

This interview was originally published at The Comics Journal.