SAFE DEPOSITS

DIGITAL MAY BE ALL THE RAGE BUT EXPERTS SAY PRESERVING OUR FILM HISTORY WILL TAKE MORE THAN 1S AND 0S

Kevin H. Martin

Five years ago, when film archival expert Milton Shefter and Andy Maltz, director, Science & Technology Council Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences (AMPAS), co-authored The Digital Dilemma, they raised the alarm that digitally stored assets may not be around for the long haul. This being Hollywood, Shefter and Maltz inevitably followed up the report with a sequel, The Digital Dilemma 2, warning of potential dangers pertaining to independent theatrical and documentary films shot and archived on digital. Shefter, best known for the creation, design and management of the Paramount Pictures Asset Protection Program, and Maltz, who led the first worldwide commercial deployment of digital cinema servers when he was CEO of Avica Technology Corporation, are no Chicken Littles – they bring decades of heavy lifting in the archival space to the table. Dovetailed with the troubling issues raised in that report are a growing number of movies originated on film that are in various states of decay, rendering the field of preservation – which includes both restoring and archiving – one of the least publicized yet most essential in the industry.

Restoration is by no means limited to 35-mm features. L.A.- based post house Cinelicious, which managing director and founding partner Paul Korver explains is known for taking on specialty projects, like the Maysles Brothers’ documentary Grey Gardens, uses a Scanity, unique among scanners for its capacity to handle 16 mm as well as an extreme dynamic range. “We can capture all the info on Vision3 stock, and it even scans high-dynamic-range black-and-white film with amazing fidelity,” Korver says. The company’s restoration of Christopher Nolan’s monochromatic 16-mm debut feature, Following, benefitted from the system’s broader depth of field, which facilitated handling of troublesome splice bumps.

For restoration projects like the Stan Brakhage collection, where the client requested output back to its original 16mm, Korver says there is no proven digital equivalent, “so we’re comparing going out to 35 millimeter and doing an optical reduction to 16 millimeter with a crop of newer 16-millimeter recording technologies – handmade solutions that are getting good word-of-mouth but need further evaluation. Outputting to 16 millimeter is unusual, but given the historic nature of Brakhage’s work, a respectful image preservation requires archiving on the smaller formats with which he worked.”

UCLA Film & Television Archive director Jan-Christopher Horak only ouputs to 35 mm because “it may well be the last surviving film format.” Horak calls digital archival techniques, which dominate European restoration efforts, shortsighted and dangerous. “There will be an eventual long-term digital solution,” he insists. “But until that time, film is the way to go.”

With 350,000 titles in UCLA’s collection – including 27 million feet of Hearst Metrotone newsreel being made available for low-res streaming – how to prioritize restorations becomes a Sophie’s Choice scenario. “We evaluate the level of deterioration, take input from colleagues in the community, and those funding restorations choose the films,” Horak explains. “UCLA’s restoration effort has been analog-only [excepting their restoration of The Red Shoes, which employed Warner’s Motion Picture Imaging to scan the original negative after removal of mold growth]. But the recent acquisition of a DaVinci Revival allows the university to work digitally as well.”

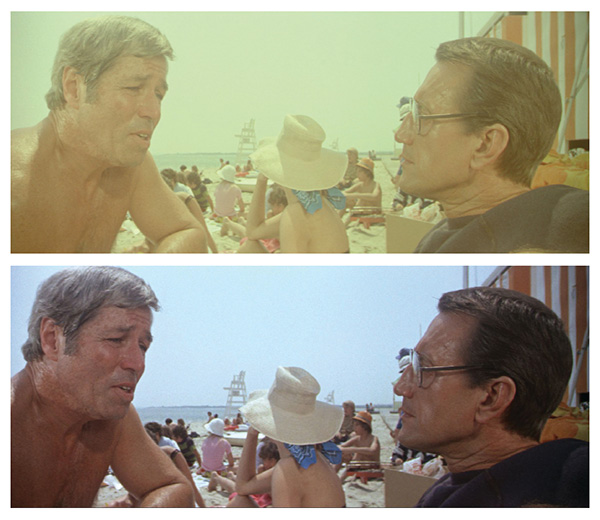

Universal Pictures has been busy restoring classics for Blu-ray, to coincide with the studio’s 100th anniversary. Thirteen recent titles have been restored in a 4K pipeline, which included outputting a new 35-mm negative. For Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (shot by Bill Butler, ASC), a 2K DCP (digital cinema package) was also output for DLP. However, before restoration could proceed, the negative was rescanned at Cineric in 4K with the scratch-reducing liquid gate process.

NBCUniversal senior VP Technical Operations Michael Daruty says existing references served as a baseline, with Spielberg giving notes on the work-in-progress. “Directors and DPs will be brought in if they choose to participate, which gives us creative signoff and a solid reference for the next time we revisit the material,” he observes.

Increased storage capacity has facilitated restoration, with Daruty noting that NBCUniversal’s file-based workflow “allows dirt removal, color correction and other restoration teams access to the film simultaneously while working in high resolution.

With damaged frames, Paintbox and Inferno artists work spatially and temporally, stealing from either side of the image or adjacent frames. Digitally captured shows are archived via film negative, with duplicate sets of master elements stored on both coasts, and established guidelines for data migration to next-generation systems strictly maintained.”

Restoration of older films is more problematic. For The Invisible Man (1933), “There was no complete existing asset,” Technicolor Creative Services Director of Restoration Services Tom Burton explains. “Every source had slugs or damaged frames, or blurs and warps at the cuts, so we had to Frankenstein a master element back together. Universal did a one-light transfer for three potential source elements, and we studied them to see if combining parts from each would work.”

Some of this stitch-in-time work took restoration into what Burton calls “visual effects meets alchemy. Our best element was missing a significant number of frames in all reels – up to six or eight in a given shot. In one very challenging shot, where complete replacement frames didn’t exist, we extracted actors from one element and the background from another, putting those frames back together like a VFX composite.” To restore Oscar’s first Best Picture winner, Wings, Technicolor worked with Paramount and AMPAS, referencing production notes from 1927 to authenticate and recreate the color process used to tint select frames.

Other technologies can be brought to bear, such as Digital Ice, which employs infrared light to remove dust and scratches. Korver says he’s exploring a tandem approach, with the Scanity’s higher-bit-rate IR camera providing a better look with Ice through the dust at the pixels beneath. “This promises to be a more accurate and archivist-minded way to restore film, because with a better picture of dirt we won’t have to rely on older methods of stealing from other frames,” he states.

Grover Crisp, Executive Vice President, Sony Pictures, Asset Management & Film Restoration, feels combining internal skill sets developed at Sony Colorworks with those of outside vendors like MTI Film has the potential to produce new solutions. “On Lawrence of Arabia we encountered problems not seen before,” Crisp states. “We are looking at the latest technologies and helping invent them if they don’t exist.” But deve loping new capabilities, while increasing options, isn’t a license to “improve” a movie in ways unintended by its makers. “We keep in mind the period in which a film was made, recognizing issues of film stocks,” Crisp adds. “We do not want to de-nature a film’s appearance and modernize it in some artificial way. The best approach is to repair, correct for decomposition and let the film be the film.”

So once a movie’s restored, then what? For all its apparent convenience, digital archival has created a number of problems, some already manifesting, others likely to do so over time. “Digital was first presented as a tool for production and post but wound up as an archival medium,” Deluxe Archive Solutions vice president Andy Pratt recalls. “I don’t think anyone grasped the ramifications of that until recently, and now studios are recognizing how valuable an archival manager will become for ensuring proper handling of assets. But there may already be a fair amount of material – especially commercials and TV programming – no longer available. Even recent films on LTO [linear tape-open] tapes are sometimes missing frames, and that’s in part due to erroneous assumptions about checksum solutions.”

Some studies indicate that archiving a digital master costs nearly twelve times as much as storing via film master; storing data from a digital production could run more than 400 times the few hundred dollars needed for an analog film, along with its audio and print records, to be safely vaulted in cold storage. Crisp says library sales are dependent on what’s in the vault. “Comparing the costs of film versus data archiving seems to be an academic activity for someone not in the business of doing it. We take the responsibility to protect the assets of the studio seriously.”

In fact, Sony’s “conservative approach” is a dual-path plan that archives data out of DI suites while continuing on-film preservation. “In a transition period of hybrid production, we create multiple copies, verify and confirm good and recoverable data, store in separate geographic locations and revisit the data for migration,” Crisp explains.

Migrating the data to newer platforms sounds like a no-brainer, yet even NASA managed to wind up with decades of unreadable data owing to successive systems falling into obsolescence before the data could be transferred. The Academy’s Science and Technology Council continues to work with industry firms on the Image Interchange Framework program in the hope that a set of global standards can be implemented.

When properly stored, film is considered a stable archival material that’s good for up to a century. But problems can still develop. Even the old standard of storing separate black-and-white masters for the Yellow, Cyan and Magenta (YCM) color records is no guarantee. “Individual YCM masters can warp at different rates and won’t fit together unless we can manipulate them back to usability,” Burton reports, noting that Technicolor’s Research and Innovation division continues to devise custom digital restoration toolsets in anticipation of such calamities while studying the even greater issues surrounding originated-on-digital shoots. “We’re looking at more than just recording the image out to film for safety; you have to store metadata, finding better ways to preserve not just the analog image, but the essence or soul of a digital movie.”

After-the-fact access to the metadata is a major concern for Total Recall DP Paul Cameron, ASC. His digital work on Collateral (2004) is relatively safe since film prints were then still common, but with the industry switching over to digital projection, film is no longer recognized as an essential commodity, and that paradigm shift has led to a digital workflow with demands that can impinge on-set processes.

“What used to be creative time between setups is now often spent making sure the look is going to be imparted properly for the next day’s viewing,” Cameron laments. “Even before we got Recall into DI at Colorworks, the metadata was no longer attached. Without LUTs, there’s no going back. That’s a big red flag for me and for the ASC. Without metadata, how can you revisit a digitally archived film and accomplish what we used to do by dialing in numbers during color timing?”

With such scenarios in mind, Technicolor and others create YCM masters from the DI data. “You wouldn’t likely use these archives to remake film negatives,” explains Burton. “But if the DI data were lost, rescanning digital YCMs and recombining those elements would recreate the DI data these records were made from.”

Since digital cameras are often run continuously during shooting, the reams of added data can become a storage issue. “As more producers begin shooting for 4K deliverables, hopefully they’ll do the math and realize that with the exception of the Red camera, 4K-resolution digital is not cheaper than film,” Korver reveals. “Every other 4K digital camera requires so much space for data that a bonded film could require over a half-petabyte of storage.”

And the trend toward 4K DIs has already begun. “It used to be only $100 million pictures could afford 4K DIs from 35 millimeter, but we’ve done two recently for films costing less than $10 million,” Korver observes. “Perhaps an incorruptible organic solution will arise within twenty years that permits inexpensive solid-state 4K masters. But since we don’t yet have that perfect digital solution in place, I certainly hope to see Kodak and film processing around for the next decade or two.”

So does the venerable Rochester firm, which recently debuted a lower-cost stock, Kodak Color Asset Protection Film 2332, specifically designed for archiving indie features, documentaries, and TV show, which capture and finish in digital formats. “File-based projects often end up stored on tapes or drives, which need to be continually re-mastered or migrated, and run the risk of format obsolescence,” concludes Kim Snyder, president of Kodak’s Entertainment Imaging Division, in a now common echo of the conclusions Shefter and Maltz reached in their Digital Dilemma reports. “The industry acknowledges the need for a long-term strategy and film is still the one true archival medium.”

– © ICG MAGAZINE Oct 2012